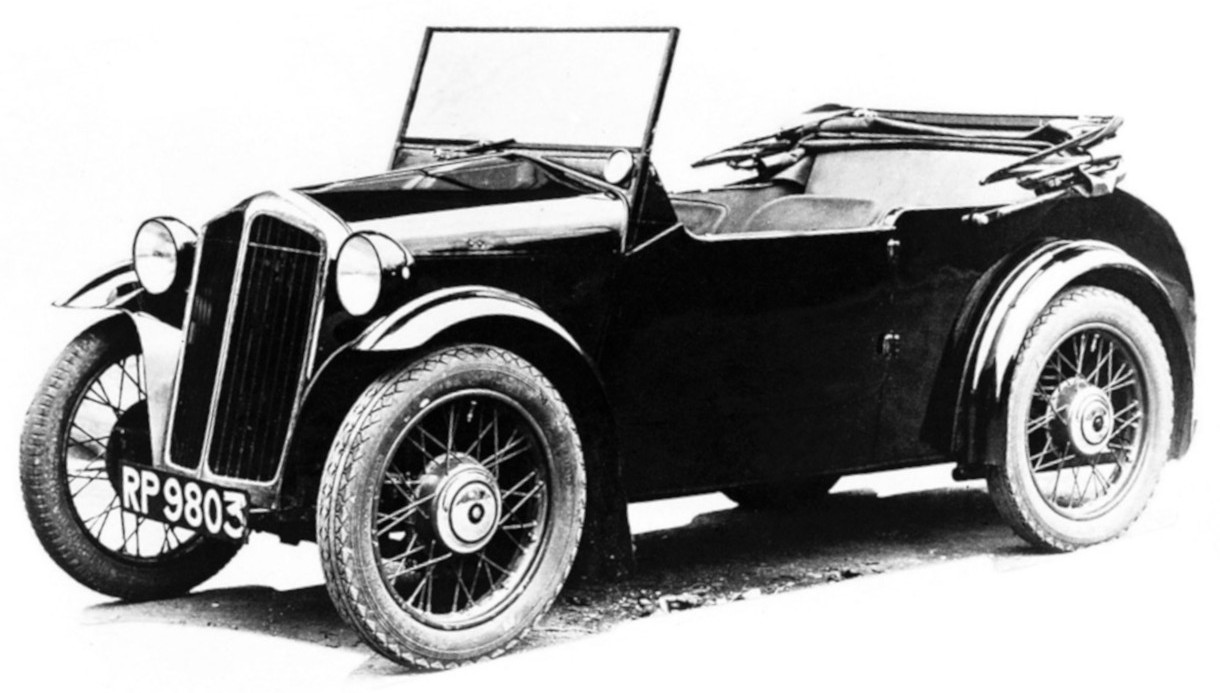

ROVER 'Scarab'

Attempt of a Small Car

1931

ROVER wanted to put a small "crawling animal" on the wheels for everyone, but rejected the request shortly after its presentation.

In the face of the Great Depression and its aftermath, Colonel Frank Searle, his time as Managing Director at ROVER, concluded that there was an urgent need for a small car in the range. He commissioned Maurice Wilks and Robert Boyle, both later key figures at Rover, to design the prototype of a rear-engined small car at his home at Braunston Hall, near Rugby, and to make a number of prototypes.

The result was the 'Scarab', which had nothing in common with the previous ROVER models. The little car had a newly designed, air-cooled, two-cylinder rear engine in a 60° V-shape, which delivered seven fiscal horsepower from a displacement of 840 cm³. Also new were the gearbox and the rear swing axle with coil springs as well as the ladder frame chassis with the front coil spring sliding column suspension. The rear pendulum half-axles were supported by a pivoting support link that gave zero roll stiffness. The four-seat tourer body consisted of a simple wooden frame clad in sheet steel. The compact dimensions still allowed for four seats, a small boot under the front bonnet, plus plug-in side rails and a simple rain cover. The whole vehicle was not to cost more than £85. This would have made the 'Scarab' the cheapest automobile on the British market, and Rover planned to sell 30,000 units a year.

Many details of the design belong to the category "pioneering and progressive". This was also the opinion of Dr Hans Nibel, then Technical Director and Chief Developer at Daimler, and his predecessor there, Ferdinad Porsche, who had in the meantime opened his own design office. They studied the 'Scarab' in detail on the occasion of the Olympic car show in London, Porsche is said to have taken constant notes. Had the 'Scarab' so unintentionally made the rear engine socially acceptable? One thinks of the Mercedes 130 (W23) with rear engine and swing axles, also of the rear-engine designs for Zündapp (Porsche Type 12) and the KdF-Wagen by Porsche.

However, the engine of the 'Scarab' was susceptible to overheating; this was countered by the installation of a double-bladed fan, which, however, did not change the engine's running, which was generally described as "rough". And the buyers for a vehicle of this class - as well as the Rover dealers - were not very enthusiastic about the 'Scarab'. After all, the Austin "Seven", a small car that looked more like a car than the newcomer on the Rover stand, had been available for years.

In an interview in Motor Sport magazine in September 1974, one of the test drivers of the 'Scarab' at the time, Mr. D. A. Cooper, recalled the car in these words:

"One day Jack Nugent, the foreman of Meteor scrutineering, said he wanted to assign a couple of men to a special job, but he couldn't say what it would be. It soon transpired that it was to check the small air-cooled 840-c.c. Vee-Twin Rover Scarab, which was to sell for 85 ₤, although the proposed price rose to nearly 100 ₤ as the project progressed and before it was eventually abandoned. (The economic crisis drove up prices then, as it does now, and the Scarab was meant to counteract that.)".

He went on to state that several drivers drove several Scarabs day and night on a 20-mile route near Coventry, each driver alternating between driving four hours and resting four hours between 6am and 10pm. ... One Scarab was fitted with an 8/45 JAP engine. The others had Rover's own Vee-Twin, housed in the rear. The test team slept in nearby quarters in a house in Willoughby. Mr Cooper recalls falling asleep in the middle of the night and putting a Scarab on its side. The main problem was that instead of a differential, a hardwood ring caused the drive of the right rear wheel to slip on sharp bends, which were consequently taken with audible grunts and crunches! The life of the tyres on the rear wheels was only about 3,000 - 4,000 miles. Larger tyres were tried but wore out after 5,000 - 6,000 miles. It was also said that the rear suspension infringed Mercedes patents. As there was no heater, driving these Scarabs was a cold affair and test drivers stuffed the pedal slots with old rags and covered the dummy radiator. Modified bodywork provided a slight improvement and a few examples, including a cut-up engine, were exhibited at the 1931 Olympia Show. ... All the experimental vehicles were registered as normal, rather than having trade plates, probably to avoid attracting unwanted attention.

For the Olympia car show, the 'Scarab' was advertised in a big way, but already at a price of £89. It is safe to assume that Rover would have made little, if any, profit on it. When Colonel Frank Searle left Rover in 1931, the Rover management decided not to put the car, which was considered "too radical" and "too Spartan", into production. This is another reason why critics today can still argue controversially about whether the car would have been "a disaster" or "a real Volkswagen" for Rover. Technically, at any rate, it was far ahead of its time. But it can be assumed that it stood in the way of the board's desire to position Rover in the automotive luxury class.

How at least the Rover publicity department saw the car can be seen in the [ ⇒ brochure text ] on the 'Scarab'.

At the Commercial Motor Show 1931, a 'Scarab' was also shown as a small delivery van. The body is said to have been side-opening only, as rear loading was considered too dangerous due to the engine in the rear. The load capacity is stated to be 5 cwt (254 kg). The price for this vehicle is given as £99 10s, picture material is unfortunately not available.

(Source: The Commercial Motor, 10 November 1931)

| Price Trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Model | £ | Remarks |

| 1931 | 85 | Preliminary reports in various magazines | |

| 1932 | 89 | From Advert, November 1931 | |

| A l l I n f o r m a t i o n w i t h o u t G u a r a n t e e | |||

| Sources | |

|---|---|

|

Rover Brochure 1931 |

|

Rover Enthusiast Magazine James Taylor June 2008 |

© 2021-2026 by ROVER - Passion / Michael-Peter Börsig

Deutsch

Deutsch